The story of a spark, a bowl of fried rice, and a dream to make languages simple.

Some ideas arrive slowly.

Others come sizzling — just like the Chao Fan I ordered on my second day in China.

The Spark

It was the year 2000 when I first brushed against Mandarin.

In a dusty corner of a library sale in Detroit, I picked up an old book on the Chinese language. I didn’t know it then, but that book would start a lifelong fascination. The Chinese characters looked like tiny artworks — expressive, meaningful, and alive.

That fascination stayed quietly with me for years, until I decided to take it seriously and flew to Suzhou, China, to study Mandarin at the university.

The Moment of Realisation — “Chao Fan”

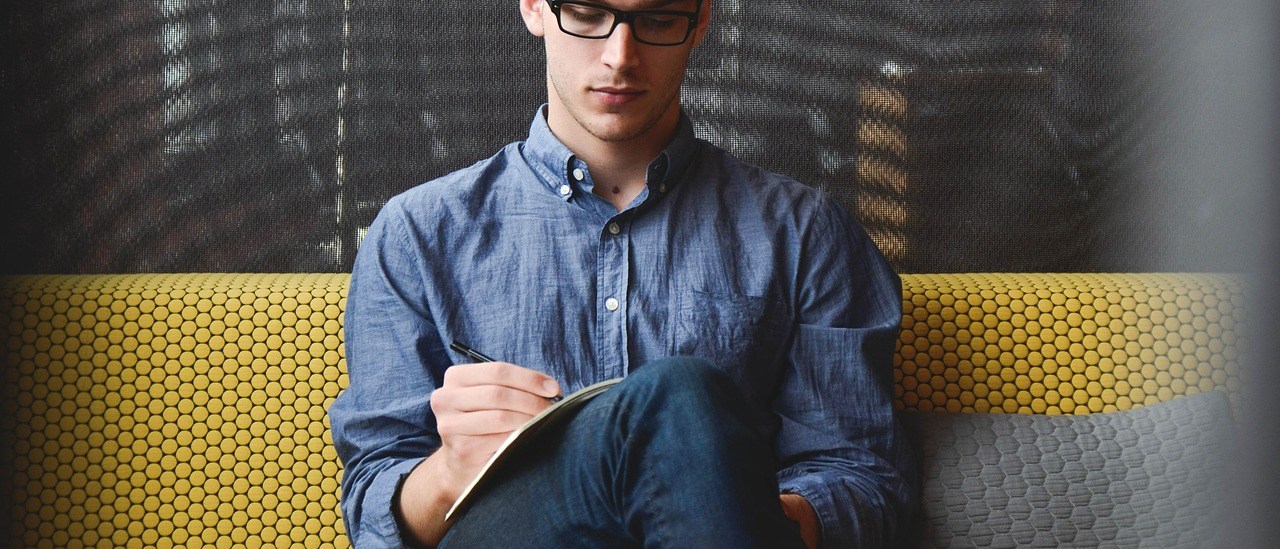

On my second day in Suzhou in 2009, I sat at a small local restaurant near the university with a blue Oxford dictionary in hand.

I wanted to order fried rice — but didn’t know how.

I flipped through my dictionary, looking up the word fried, thinking I could somehow combine it with rice. I planned to show the waitress a frying action to help her understand.

But when I looked up the word, I froze.

The translation was Chao.

And Chao Fan — that exact sound — was what the waitress was saying all along.

At that moment, something clicked.

I realised that Chao Fan (fried rice) and Chao Mian (fried noodles) sounded a lot like the Chowmein we say in India.

And that was my aha moment.

It was my first glimpse of how language doesn’t always have to feel foreign — sometimes, it’s just waiting to be connected to something we already know. That tiny spark in a bustling Suzhou café would one day shape The Oriental Dialogue’s entire teaching philosophy: start with the familiar, and lead learners to the new.

Discovering Culture Through Language

Studying Mandarin in China was a revelation.

I realised that the language wasn’t rigid or distant — it flowed with life, emotion, and culture.

And surprisingly, it felt a lot like Indian languages. The tones, expressions, and emphasis on context made it feel natural, not alien.

I also noticed that most textbooks were designed for Western learners. Indians, I felt, had an edge — our linguistic diversity, flexible thinking, and cultural nuances made it easier for us to learn Chinese if it was taught our way.

That realisation stayed with me — quietly shaping my thoughts, even when life took me elsewhere.

A Detour and a Calling

After returning to India, I joined one of the largest banks as an officer — a wonderful opportunity that I embraced wholeheartedly.

But Mandarin, for a while, took a back seat.

Years later, I was asked to conduct a demo class. I agreed confidently — and realised, with a sinking feeling, that I’d forgotten almost everything I once knew. The demo didn’t go well. But that evening, I knew exactly where I belonged.

I wanted to make languages simple, accessible, and joyful — not intimidating.

The First Class and the “Chowmein” Start

When I began teaching, I returned to that Suzhou memory — Chao Fan, Chao Mian, Chowmein.

I thought — what if I start my very first class with that?

So, that’s what I did.

The session began with food — Hakka Chowmein, something every Indian relates to. I explained that Chao Mian means “fried noodles.”

Within 15 minutes, my students had learned five new Mandarin words without even realising it.

It wasn’t just language — it was discovery, laughter, and connection.

That class set the tone for what The Oriental Dialogue would become — a place where language is lived, not memorised.

The Foundation

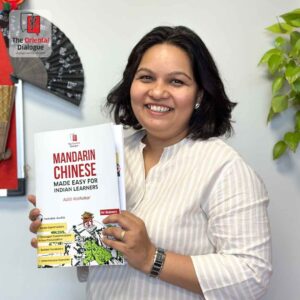

I developed a 16-hour Business Mandarin course for professionals travelling to China — teaching greetings, directions, prices, introductions, and simple negotiations.

To reach more learners, I joined the Mahratta Chamber of Commerce (MCCIA) in Pune and conducted my first workshops. They weren’t financially rewarding, but they gave me what money couldn’t — belief.

Students loved the simplicity and practicality of the sessions.

That encouragement pushed me to formalise my teaching approach.

The Birth of The Oriental Dialogue

In 2016, The Oriental Dialogue was officially born — built on a single idea:

In 2016, The Oriental Dialogue was officially born — built on a single idea:

“Anything can be made easy if it’s taught with heart and connection.”

We created a structured system — Beginners → Level 1 → Level 2, blending everyday conversation with HSK readiness.

Soon, students began travelling hours to attend our classes. To make it easier, we started online batches in November 2016, long before virtual learning became common.

Growth, Expansion, and New Languages

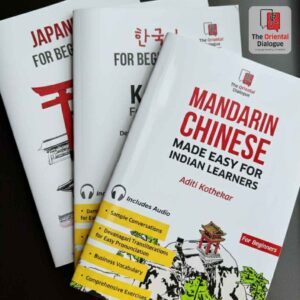

By 2018, The Oriental Dialogue had a new look — logo, website, and identity — and new languageS: Korean and Japanese.

Students began excelling in HSK exams, and corporate trainings grew.